Sacred Texts Judaism Index Previous Next

Buy this Book at Amazon.com

Jewish Magic and Superstition, by Joshua Trachtenberg, [1939], at sacred-texts.com

ONE of the most popular of magical devices was the amulet, worn upon the person or attached to objects and animals (the Hebrew word for amulet, kame‘a, has the root meaning "to bind") . Even in our supposedly non-superstitious age the good-luck charm is still quite familiar, apologetically displayed on watch-chain, or carried furtively in the recesses of pockets and purses—the rabbit's foot, the horseshoe, lucky coins, rings engraved with Chinese or Hebrew letters, animal molars. How much more common, then, are such objects in societies which unashamedly and openly accept them for what they are, whether in the less sophisticated regions of our contemporary world, or in the medieval and ancient worlds, which did not for a moment doubt their efficacy! As a matter of fact, it has been suggested that all ornaments worn on the person were originally amulets.

Primitive religions make much of these peculiarly potent objects, and the Biblical Hebrews were well acquainted with their merits. Their use was very extensive in the Talmudic period, and, accepted by the rabbinic authorities, impressed itself strongly upon the habits of later times. Jewish amulets were of two sorts: written, and objects such as herbs, foxes’ tails, stones, etc. They were employed to heal or to protect men, animals, and even inanimate things. We find the same types in use during the period of the Talmud and in the Middle Ages, though, of course, the intervening centuries and cultural contacts made for a greater variety. There was no legal prohibition against the use of such charms. In fact, the rules which were set up to distinguish proper from improper amulets lent them a definite degree of acceptance; though some rabbis frowned upon them, or urged the danger of preparing them, others actually suggested their use on certain occasions, and the common folk was very

much addicted to this particular form of magic. Amulets were the favored Jewish magical device during the Middle Ages, and the fact that they were predominantly of the written type, prepared especially for specific emergencies and particular individuals, enhanced their magical character.1

The material objects that were employed as amulets because of their fancied occult power, were no doubt many more in number and variety than the literature discloses. The Talmud mentions several, and references to these are frequent in our sources, but it is difficult to determine whether these remarks reflect a contemporaneous use of the same charms. In this category were the fox's tail, and the crimson thread which was hung on the forehead of a horse to protect him against the evil eye. But a current fable of a too wily fox indicates that the virtues of the fox's tail, as well as other parts of his body, were known and probably utilized by medieval Jews. It seems that the fox had invaded a walled town, and when he was ready to depart found the gates closed. He decided to play dead in the hope that his carcass would be carted away to the garbage dump outside the walls. Along came a man who mused, "This fox's tail will do as a broom for my house, for it will sweep away demons and evil spirits," and off came the tail. Another man stopped and decided, "Here! This fox's teeth are just the thing to hang around my baby's neck," and out came the teeth. When a third passer-by made ready to skin the poor creature, the game got too strenuous and master Reynard came to life in a wild dash. The tale has more than one moral, for our purpose. As to the thread, red is a color regarded everywhere as anti-demonic and anti-evil eye, and in the Middle Ages we find Jewish children wearing coral necklaces, just as Christian children did, to protect them against the malevolent jettatura. Herbs and aromatic roots were also mentioned often as potent amulets. Fennel, for instance, was pressed into service against hurt of any nature, as this Judeo-German invocation indicates: "Un’ wer dich treit [trägt] unter seinem gewande, der muss sein behüt’, sein leib un’ sein gemüt, von eisen un’ von stahel, un’ von stock un’ von stein, un’ vor feuer un’ vor wasser, un’ vor aller schlimme übel, das da ê [ehe] geschaffen wart, sint Adam gemacht wart. Das sei wahr in Godes namen. Amen." 2

A Talmudic amulet which was widely employed in medieval times—it was well known to non-Jews also—was the so-called even tekumah, the "preserving stone," which was believed to prevent

miscarriage. The Talmud does not tell us just what sort of stone this was. Several medieval writers were more informative, but unfortunately they employed one or perhaps several French equivalents whose meanings in Hebrew transliteration are not altogether clear, but which show that these were in common use. One writer went into some detail: "This stone is pierced through the middle, and is round, about as large and heavy as a medium sized egg, glassy in appearance, and is to be found in the fields," he explained. The French terms seem to indicate a hollow stone within which is a smaller one, a sort of rattle (perhaps the eaglestone or ætites); a later commentator calls it a Sternschoss (meteoroid).3

A man born with a caul was counselled to keep it on his person throughout his life as a protection against the demons who battle during a storm. A phallus-shaped stone inscribed with the Hebrew words "accident of sleep" and the words of Gen. 49:24, "But his bow abode firm" is to be seen in the Musée Raymond in Toulouse. Its intention is unmistakable; similar amulets must have been in use in Germany. Toward the end of the Middle Ages, if not earlier, there arose the custom of employing a piece of the Afikomen, a specially designated cake of unleavened bread at the Passover Seder, as an amulet, hanging it in the house, or carrying it in a pouch, to protect one against evil spirits and against evil men. A metal plate inscribed with the letter heh (a sign for the Tetragrammaton), worn about the neck, was no doubt another such amulet, despite the ritualistic explanation it received; similar charms are still in use today. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries we find references to charms which, by their nature, and by virtue of the prominence of German words in the text, seem to have been borrowed from non-Jews. Among these I may mention the following: To find favor in people's eyes, carry the right eye or ear of an animal on your person. To obtain a favorable hearing from a judge, get a straw in which there are three nodes, and place the middle node under your tongue in the morning; or else, place henbane (hyoscyamus) seeds, still in their husks, in your hair above the forehead. A charm that will put an insomniac to sleep is prepared thus: one must secure a louse from the head of the patient and induce it to crawl into a bone which has a hole in it, seal the hole, and hang the imprisoned insect on the patient's neck. An amulet that gives protection consists of a sprig of fennel over which an incantation has been recited and which has then been wrapped in silk, together with some wheat and coins, and

then encased in wax. Other amulets, such as rings and medallions of various sorts, were no doubt similarly employed, for Jews had a reputation as metal-workers and engravers.4

Objects of this sort were used for more or less esoteric reasons. Sometimes the reputation for occult virtue outlived the original reason. Often what was involved was a sympathetic transference of the qualities and characteristics of the object to the wearer. In the case of the color red, for instance, it has been suggested that its magical power derives from its association with the blood of sacrifice, for which it is a substitute, and therefore it appeases the powers of evil. On the other hand, parts of an animal convey the special qualities of strength, or cunning, or courage which distinguish it. The stone within a stone represents the embryo in the womb; just as the one is securely imprisoned, so may the other be. This type of sympathetic amulet is well known and universally employed. Despite the paucity of evidence in our sources, medieval Jewry must have drawn extensively upon Jewish tradition and its non-Jewish neighbors for a multitude of such charms.5

An interesting instance of confidence placed in a non-Jewish talisman is afforded by a statement in a fifteenth-century work, Leket Yosher: "I recall that when my son Seligmann was born I had my wife make him a linen shirt, called a Nothemd in German, which everybody says protects the wearer against assault on the highway (but I myself was once attacked while I was wearing one, though, truth to tell, I'm not certain that another shirt wasn't substituted for it)." The writer's description of the Nothemd (also called Sieghemd, St. George's Shirt) is hardly satisfying: "It is square, with a hole in the center," is all he says; but contemporaneous Christian sources fill out his account. It seems that this type of shirt possessed a host of magical properties—it served as protection against weapons and accidents and attack, it procured easy and quick delivery of children, victory in warfare and in courts of law, immunity from sorcery, etc. One version of its manufacture required that it be made by girls of undoubted chastity, who must spin the thread from flax, weave it and sew it in the name of the devil on Christmas night. Two heads were embroidered on the front, the right with a long beard and a helmet, the left bristly and crowned with a devil's headdress. On either side of the figures was a cross. In length the shirt extended from the head to the waist. According to other accounts (which omit the diabolic features) it was woven and sewn by a pure

girl on Sundays (or on Christmas nights) over a period of seven years, during which she remained mute all the time. This was the nature (substituting Jewish forms for the Christian) of the Nothemd which our authority hoped would shield his first-born from the hazards of life.5a

Precious and semi-precious stones, in particular, have been credited with superior occult powers by many peoples. In medieval Europe this was an unquestioned dogma of the religion of superstition, as well as a subject of theological speculation; a heated debate centered about the question whether their peculiar virtues were divinely implanted, or simply part of the nature of gems. Jews were the leading importers of and dealers in gems during the early Middle Ages, and Christian Europe attributed to them a certain specialization in the magic properties of precious stones: Christianos fidem in verbis, Judæos in lapidibus pretiosis, et Paganos in herbis ponere, ran the adage.

Indeed, there was good warrant in the Jewish background for such a specialty. The Bible (Ex. 28:17-20) speaks of the twelve gems, engraved with the tribal names, which were set into the High Priest's breastplate, leaving room for much mystical speculation in the later literature on the various aspects of these gems. But strangely enough the discussion limited itself to the mystical significance of the twelve gems, and touched hardly at all upon their magical properties. This subject seems to have been altogether out of the line of Jewish tradition and interest—though Jews were acquainted with it. The Talmud, for instance, remarks that Abraham possessed a gem which could heal all those who looked upon it. Such comments, however, are comparatively rare in Jewish literature. Like many other Christian ideas about the Jews, their reputation as experts in the magic virtues of gems was far wide of the mark. As Steinschneider remarks, "Hardly a single dissertation on this subject is to be found in Hebrew literature . . . and the little that does exist is very insignificant and recent, derived mainly from non-Jewish sources."6 In the Hebrew literature of Northern Europe I have found only one discussion of the properties of precious stones, and that in the unpublished fourteenth-century manuscript, Sefer Gematriaot. While it unquestionably drew upon non-Jewish material, it

acquired a definitely Jewish coloration in its cross-cultural journey, and is built upon the scheme of the twelve tribal gems. I give here a partial translation of the passage, the complete text of which may be found in Appendix II.7

"Odem [commonly translated carnelian, ruby] appertains to Reuben. . . . This is the stone called rubino. Its use is to prevent the woman who wears it from suffering a miscarriage. It is also good for women who suffer excessively in child-birth, and, consumed with food and drink, it is good for fertility. . . . Sometimes the stone rubino is combined with another stone and is called rubin felsht. . . .

"Pitdah [commonly, topaz] the stone of Simeon. This is the prasinum (?) but it seems to me it is the smeralda (?); it is greenish because of Zimri, the son of Salu (Nu. 25:14) who made the Simeonites green in the face . . . and it is dull in appearance because their faces paled. Its use is to chill the body. . . . Ethiopia and Egypt are steeped in sensuality, and therefore it is to be found there, to cool the body. It is also useful in affairs of the heart. . . .

"Bareket [emerald or smaragd] This is the carbuncle, which flashes like lightning [barak] and gleams like a flame. . . . This is the stone of Levi. . . . It is beneficial to those who wear it; it makes man wise, and lights up his eyes, and opens his heart. Taken as a food in the form of powder with other drugs it rejuvenates the old. . . .

"Nofech [carbuncle] This is the smaragd. . . . It is green, for Judah's face was of a greenish hue when he mastered his passion and acknowledged his relations with Tamar (Gen. 38) . . . . This stone is clear, and not cloudy like Simeon's, for when he was cleared of the suspicion of Joseph's death his face grew bright with joy. The function of this stone is to add strength, for one who wears it will be victorious in battle; that is why the tribe of Judah were mighty heroes. It is called nofech because the enemy turns (hofech) his back to the one who wears it, as it is written, 'Thy hand shall be on the neck of thine enemies' (Gen. 49:8) .

"Sapir [sapphire] the stone of Issachar, who 'had understanding of the times' (I Chr. 12:32) and of the Torah. It is purple-blue in color, and is excellent to cure ailments, and especially to pass across the eyes, as it is said, 'It shall be health to thy navel, and marrow to thy bones' (Prov. 3:8).

"Yahalom [emerald] This is the stone of Zebulun; it is the jewel called perla. It brings success in trade, and is good to carry along on

a journey, because it preserves peace and increases good-will. And it brings sleep, for it is written, 'Now will my husband sleep with me (yizbeleni)' (Gen. 30: 20).

"Leshem [jacinth] This is the stone of Dan, which is the topaẓiah. The face of a man may be seen in it, in reverse, because they overturned the graven image of the idol (Jud. 18) .

"Shebo [agate] This is the stone of Naphtali, which is the turkiska. It establishes man firmly in his place, and prevents him from stumbling and falling; it is especially coveted by knights and horsemen, it makes a man secure on his mount. . . .

"Aḥlamah [amethyst] . . . This is the stone called cristalo; it is very common and well known. It is the stone of Gad, because the tribe of Gad are very numerous and renowned. . . . There is another gem called diamanti which is like the cristalo, except that it has a faintly reddish hue; the tribe of Gad used to carry this with them. It is useful in war, for it buoys up the heart so that it doesn't grow faint, for Gad used to move into battle ahead of their brothers. . . . This stone is good even against demons and spirits, so that one who wears it is not seized by that faintness of heart which they call glolir (?) .

"Tarshish [beryl] This is the yakint [jacinth]; the Targum calls it the 'sea-green,' which is its color. It is the stone of Asher. Its utility is to burn up food. No bad food will remain in the bowels of one who consumes it, but will be transformed into a thick oil. For it is written, 'As for Asher, his bread shall be fat' (Gen. 49:20). . . . Sometimes the sapphire is found in combination with the yakint, because the tribes of Asher and Issachar intermarried. . . . Because the bread of Asher is fat for all creatures, and the faces of stout people are ruddy, the yakint is sometimes of a reddish hue.

"Shoham [onyx] This is the stone called nikli [nichilus, an agate]. It is Joseph's stone and it bestows grace. . . . One who wears it at a gathering of people will find it useful to make them hearken to his words, and to win success. . . .

"Yashfeh [jasper] This is Benjamin's; it is called diaspi, and is found in a variety of colors: green, black, and red, because Benjamin knew that Joseph had been sold, and often considered revealing this to Jacob, and his face would turn all colors as he debated whether to disclose his secret or to keep it hidden; but he restrained himself and kept the matter concealed. This stone yashfeh, because it was a bridle on his tongue, has also the power to restrain the blood. . . ."

These charms did not at all contest the far greater popularity of the written amulets, which contained the most powerful elements of Jewish magic—the names. Prepared by experts to meet particular needs, those of which we have a record differed widely in detail, but in general conformed to the underlying scheme of the incantation. There were some which consisted exclusively of Biblical quotations with or without the names that were read into them. Copies of Ps. 126, for instance, with the addition of the anti-Lilitian names, Sanvi, Sansanvi, Semangelaf, placed in the four corners of a house, protect children against the hazards of infancy; Ps. 127, hung about a boy's neck from the moment of birth, guards him throughout life. Or the inscription might consist exclusively of angel-names.8 But these were comparatively rare. Most of the written amulets contained the combination of elements which centuries of usage had impressed upon this magical form.

The following text of a typical amulet, guaranteed to perform a very wide range of functions, will serve to illustrate the species:9

"An effective amulet, tested and tried, against the evil eye and evil spirits, for grace, against imprisonment and the sword, for intelligence, to be able to instruct people in Torah, against all sorts of disease and reverses, and against loss of property: 'In the name of Shaddai, who created heaven and earth, and in the name of the angel Raphael, the memuneh in charge of this month, and by you, Smmel, Hngel, Vngsursh, Kndors, Ndmh, Kmiel, S‘ariel, Abrid, Gurid, memunim of the summer equinox, and by your Prince, Or‘anir, by the angel of the hour and the star, in the name of the Lord, God of Israel, who rests upon the Cherubs, the great, mighty, and awesome God, yhvh Ẓebaot is His name, and in Thy name, God of mercy, and by thy name, Adiriron, trustworthy healing-God, in whose hand are the heavenly and earthly households, and by the name yhvh, save me by this writing and by this amulet, written in the name of N son of N [mother's name]. Protect him in all his two hundred and forty-eight organs against imprisonment and against the two-edged sword. Help him, deliver him, save him, rescue him from evil men and evil speech, and from a harsh litigant, whether he be Jew or Gentile. Humble and bring low those who rise against him to do him evil by deed or by speech, by counsel or by thought. May all who seek his harm be overthrown, destroyed,

humbled, afflicted, broken so that not a limb remains whole; may those who wish him ill be put to shame. Save him, deliver him from all sorcery, from all reverses, from poverty, from wicked men, from sudden death, from the evil effects of passion, from every sort of tribulation and disease. Grant him grace, and love, and mercy before the throne of God, and before all beings who behold him. Let the fear of him rest upon all creatures, as the mighty lion dreads the mightier mafgi‘a [cf. Shab. 77b]. I conjure N, son of N, in the name of Uriron and Adriron (sic) . Praised be the Lord forever. Amen and Amen.'"

The elements that stand out in this text are: 1. most important, the names of God and of angels; 2. the Biblical expressions or phrases, descriptive of God's attributes, or bespeaking His protection and healing power, such as "yhvh Ẓebaot is His name," "who rests upon the Cherubs," etc.—these are more manifest in other amulet texts than in this one, but in less elaborate texts they are dropped altogether; 3. the meticulousness with which the various functions of the amulet are detailed; 4. the name of the person the amulet is meant to serve, and his mother's name.10

Not all amulets were so long, or so complicated, or so inclusive as this one, but almost all included these four elements. Where the charm was to perform a single function, it was, of course, much simpler, but did not differ essentially from the sample given. As Sefer Raziel stressed, one must be careful to include the names of the angels that are in control of the immediate situation, and which have the specialized powers it is desired to call into operation. A charm intended to heal or ward off a particular ailment should specify the name of the demon that is responsible, if it is known. As an instance of a much simpler amulet, which, while omitting the Biblical phrases, fulfills the other requirements, I may cite the following formula:

"To win favor, write on parchment and carry on your person: 'Ḥasdiel at my right, Ḥaniel at my left, Raḥmiel at my head, angels, let me find favor and grace before all men, great and small, and before all of whom I have need, in the name of Yah Yah Yah Yau Yau Yau Yah Zebaot. Amen Amen Amen Selah.'"11

In addition to the written inscription amulets were also often adorned with magical figures. Among these may be singled out the pentagram (popularly identified as the "Seal of Solomon") and the hexagram. The hexagram in particular has acquired a special

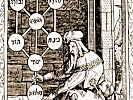

Click to enlarge

TWO MEDIEVAL AMULET TEXTS

Courtesy of the Jewish Theological Seminary Library, New York

Two Medieval Amulet Texts: Upper Portion, "For Grace and Favor"; Lower Portion, "To Safeguard A Man Against All Weapons."—From Sefer Raziel, Amsterdam, 1701.

place in Jewish affections, and is regarded as the symbol of Judaism, under the name "Shield of David." So strong has the connection between this seal and the Jewish people become that it seems today to have behind it centuries of traditional usage. It may surprise some readers, then, to learn that only in the past hundred years or so has the Magen David been widely accepted and used by Jews as symbolic of their faith, in the sense that the cross and crescent are of Christianity and Mohammedanism. The hexagram, in fact, has no direct connection with Judaism. Both these figures are the common property of humankind. The Pythagoreans attributed great mystical significance to them; they played a mystical and magical rôle in Peru, Egypt, China, and Japan; they are to be found in Hellenistic magical papyri; the Hindus used the hexagram and pentagram as potent talismans; they occur often in Arabic amulets, and in medieval Christian magical texts; in Germany, where it is called the Drudenfuss, the pentagram may still be seen inscribed on stable-doors and on beds and cradles as a protection against enchantments. Their magical virtues were known in Jewish circles at an early time; they are to be found often in early post-Talmudic incantations, and occur fairly often in medieval amulets and mezuzot. Names of God and Biblical texts were frequently inscribed within the triangles of the magical hexagram.12

Of another sort, but equally widely employed in Jewish amulets, was a series of figures constructed by joining straight and curved lines tipped with circles, in this manner:

[paragraph continues] Interspersed among these are to be found circles, spirals, squares and other geometric forms. Figures of this order appear in early Aramaic amulets. What their original purpose or nature was it is difficult at present to determine. Were they merely intended to mystify, or did they possess some meaning? Several medieval writers constructed magical alphabets by allotting a sign to each of the Hebrew letters, but unfortunately no two of these alphabets correspond, nor are they of any help in deciphering amulet inscriptions. One must conclude that these alphabets were individual creations which, instead of being the source of these signs, were inspired by them. These figures appear in small groups, or in wild profusion, at the end of amulet

texts, depending upon the ingenuity of the magician. Some amulets consist entirely of such signs, with no written text at all. The following charm illustrates all the elements:13

"An amulet for grace and favor; write upon deer-skin: 'By Thy universal name of grace and favor yhvh, set Thy grace yhvh upon N, son of N, as it rested upon Joseph, the righteous one, as it is said, "And the Lord was with Joseph, and showed kindness unto him, and gave him favor" in the sight of all those who beheld him [Gen. 39:21]. In the name of Michael, Gabriel, Raphael, Uriel, Kabshiel, Yah (repeated eight times), Ehyeh, Ahah (four times), Yehu (nine times)'

Concerning still another amulet type it is difficult to speak with assurance. The earliest northern Jewish record of it seems to have come to us from the sixteenth or seventeenth century, though it was mentioned by Abraham ibn Ezra in the twelfth. Yet there is little doubt that it must have been known in the North quite as early. This is the Zahlenquadrat, or "magic square," a square figure formed by a series of numbers in arithmetic progression, so disposed in parallel and equal rows that the sum of the numbers in each row or line taken perpendicularly, horizontally, or diagonally, is equal. It looks simpler than it sounds:

[paragraph continues] This is the simplest of these figures; others comprise sixteen boxes, 25, 36, etc. Agrippa von Nettesheim (1486-1535) in his De Occulta Philosophia gave these number-squares a special astrological significance, associating each with a planetary deity, in which form they became very popular among Christian Kabbalists and magicians. The numerals in these Christian amulets, of which quite a few

are in existence, are frequently in Hebrew, and as a result there has been a tendency to regard them as Jewish. There can be no question, however, despite the Hebrew (Christian magic often employed Hebrew characters) that these astrological amulets, if employed by Jews at all, were so used only after Agrippa had developed his system, and reflected Christian practice.14

Leaving aside, then, the late astrological aspect of these number-squares, we find that the simple figure of nine fields, given above, has had a long and varied career in the history of magic. It was highly regarded by the ancient Chinese and Hindus, and is frequently encountered in Arabian magic. For Jews it must have possessed an especially potent character, for apart from its background in Oriental magic, and the mystical light which the Pythagorean theories cast upon its combination of numerals, the Hebrew letters which Jews employed as numerals had particular magical importance: the heart of the figure, the number five, is the Hebrew letter heh, which also serves as a symbol of the Tetragrammaton, while the sum, fifteen, is in Hebrew Yah, a particle of that name, and independently important as a powerful name of God. An examination of the manuscript material in European collections should disclose some examples of it.

Judaism officially countenanced the use of amulets to heal and to prevent disease, as well as to protect the individual. The presence in them of mystical names and quotations from the Bible even raised the difficult issue of their "sacred" character. They were regarded as sufficiently "sacred" not to be worn in a privy, unless encased in a leather pouch, and yet not "sacred" enough to warrant being saved from a fire on the Sabbath. The question arose, furthermore, whether they might be carried on the Sabbath, when it was forbidden to have on one's person anything that could be technically included in the category of burdens, and when it was also forbidden to apply remedies except in cases of serious illness.

The popular addiction to this form of magic was so strong that it was futile to prohibit altogether the use of amulets on the Sabbath, and instead a set of rules was created which distinguished between effective and "approved" (literally, "expert, experienced") amulets, which might be worn on that day, and those technically classed as

unapproved. According to these rules, an amulet prepared for a specific function, which had been successfully employed by three different persons, was "approved" as equally effective for all, and an expert who had written three different amulets which had been tested by three individuals was himself "approved," and the products of his skill were permitted to all. Such amulets might be worn on the Sabbath, others not. These principles were established in the Talmud, and were frequently reiterated in the medieval literature. Medieval authorities were willing to forego a test in the case of recognized physicians: amulets written by a "rechter doktor, der gewiss is’, un’ gedoktrirt is’" were automatically "approved" as coming within these provisions. Their necessity was explained in this wise: were the effectiveness of the amulet, or the writer, to rest solely upon a test made in a single case, the cure might be attributable to the "star" of the patient or physician, rather than to the amulet itself. None the less, however insistently these rules were repeated by the rabbis, popular observance was lax. Even the authorities did not forbid the wearing of "unapproved" amulets on weekdays, though this was the subtle purpose of the legislation, and the rabbinic responsa indicate that they were freely worn on the Sabbath as well. The lust for miracles was more compelling than religious scruple, and rabbinic regulation of the amulet industry was as often honored in the breach as in the observance.15

Besides these official regulations there grew up certain generally accepted rules affecting the writing of amulets. While various materials are mentioned, such as several types of parchment, metals, clay, etc., the one most commonly used and expressly preferred was a parchment made from deer-skin. The prescription of ritual and physical cleanliness and purity applied to writers of amulets as well as to other practitioners of Jewish magic, and the formulas frequently specify that the parchment must be kosher, that is, ritually acceptable. Emphasizing the religious character of amulets was the benediction, on the order of those prescribed in the liturgy, to be recited before writing one: "Praised be Thou, Lord, our God, King of the universe, who hast sanctified Thy great and revered name, and revealed it to the pious ones, to invoke Thy power and Thy might by means of Thy name and Thy word and the words of Thy mouth, oral and written. Praised be Thou, Lord, King, Holy One; may Thy name be ever extolled."16

Lest the writing of amulets be mistaken for a wholly religious act, however, a further element interposed to reveal its fundamentally superstitious character. Not all times were fitting for the task, if success was to be assured. Sefer Raziel17 provides us with a table of hours and days which are most propitious for this exercise—a table which evidence from other sources proves was generally accepted: Sunday, the seventh hour (the day began at about six the preceding evening), Monday, the fifth, Tuesday, the first, Wednesday, the second, Thursday, the fourth, Friday, the fifth and tenth hours. As to the days of the month, to give all the information for those who may have occasion to use it: amulets may be written at any time during the day on the 1st, 4th, 12th, 10th, 22nd, 25th, 28th; in the evening only on the 17th; in the morning only on the 2nd, 5th, 7th, 8th, 11th, 14th, 16th, 21st, 24th, 27th, 30th; and not at all on the remaining days. These times were selected as especially propitious, or the reverse, because of the astrological and angelic forces which were then operative.

Two ritual objects of ambiguous character, the phylacteries and the mezuzah, played a part in superstitious usage as well as in religious. The phylacteries undoubtedly developed from some form of amulet or charm, and while their religious nature was already firmly impressed upon them, the Talmud still retained reminiscences of their magical utility in several statements which indicate that they were popularly believed to drive off demons. A prominent rabbi braved the displeasure of his colleagues and wore them in the privy, which was believed to be demon-infested; and in the Middle Ages as well as in Talmudic times they were placed upon a baby who had been frightened out of his sleep by demons. But the effect of religious teaching and custom, and perhaps also the fact that until the thirteenth century the manner of performing the rite and the composition of the phylacteries were far from standardized, so that the entire matter was a moot theological issue, in this case made for a triumph of religion over superstition. During the medieval period there is hardly a sign that they were still regarded as anti-demonic (their use to calm restless infants was unquestionably a reflex of the Talmudic practice) . True, we read at times that the tefillin ward

off the unwelcome ministrations of Satan—but the sense is figurative: the pious man who fulfills the minutiæ of ritual need not fear the powers of evil.18

The mezuzah, on the contrary, retained its original significance as an amulet despite rabbinic efforts to make it an exclusively religious symbol. Descended from a primitive charm, affixed to the door-post to keep demons out of the house, the rabbinic leaders gave it literally a religious content in the shape of a strip of parchment inscribed with the Biblical verses, Deut. 6:4-19, 11:13-20, in the hope that it might develop into a constant reminder of the principle of monotheism—a wise attempt to re-interpret instead of an unavailing prohibition. But the whitewash never adhered so thickly as to hide the true nature of the device. In the Middle Ages it is a question whether its anti-demonic virtues did not far outweigh its religious value in the public mind. Even as outstanding an authority as Meir of Rothenburg was unwary enough to make this damaging admission: "If Jews knew how serviceable the mezuzah is, they would not lightly disregard it. They may be assured that no demon can have power over a house upon which the mezuzah is properly affixed. In our house I believe we have close to twenty-four mezuzot." Solomon Luria reports that after R. Meir had attached a mezuzah to the door of his study, he explained that "previously an evil spirit used to torment him whenever he took a nap at noon, but not any longer, now that the mezuzah was up." With such weighty support it cannot be wondered at that the masses followed R. Meir's way of thinking. Isaiah Horowitz further dignified the proceeding by making it emanate from God Himself. "I have set a guardian outside the door of My sanctuary [the Jewish home]," the deity proclaims, "to establish a decree for My heavenly and earthly households; while it is upon the door every destroyer and demon must flee from it."19

So potent did the mezuzah become in the popular imagination that its powers were extended to cover even life and death. A Talmudic statement, expounding the Biblical promise, "that your days may be multiplied," has it that premature death will visit the homes of those who fail to observe the law of the mezuzah meticulously; in the Middle Ages the literal-minded took the Talmud at its word, and seized upon the pun in the Zohar which split mezuzot into two words, zaz mavet, "death departs," as ample authority for their view that every room in a house should be guarded by a mezuzah.

In more recent times, when a community was wasted by plague, its leaders inspected the mezuzot on the doorposts to discover which was improperly written and therefore responsible for the visitation. The mezuzah has even come off the doorposts; during the World War many of the Jewish soldiers carried mezuzot in their pockets to deflect enemy bullets; it has today become a popular watch-charm among Jews.20 I have even been told of a nun who dropped her purse one day, and among its contents, scattered on the ground, was—a mezuzah!

Non-Jewish recognition of the magic powers of the mezuzah is not, however, a modern phenomenon. According to Rashi, pagan rulers long ago suspected Jews of working magic against them when they affixed the little capsules to their doors. And, as we have seen, some Christian prelates in the Middle Ages were eager to place their castles, too, under the protection of the humble mezuzah.21

If we turn now to the mezuzah itself,22 the rules relating to its preparation, and its contents, we are confronted with striking evidence of the extent to which it had become an amulet, pure and simple, in the Middle Ages. The prescription of a high degree of cleanliness and ritual purity preparatory to writing it, while pertinent to its sacred character as an extract from Holy Writ, was none the less of the same nature as that which appertained to the amulet. It was to be transcribed preferably on deer parchment, and the hours which were best suited for its successful preparation correspond with the amulet table given in Sefer Raziel, as well as the astrological and angelic influences which were called into play at these times. According to a frequently quoted passage attributed to the Gaon Sherira (tenth century): "It is to be written only on Monday, in the fifth hour, over which the Sun and the angel Raphael preside, or on Thursday, in the fourth hour, presided over by Venus and the angel Anael." This passage, and many others, lumped together mezuzot, tefillin, and amulets—indicating that the three were generally regarded as possessing the same essential character.

Rashi stated that both mezuzot and amulets contained in common a special type of "large letters," which were peculiar to them. A later commentator suggested that these were in the ancient Hebrew script, but we have no text of an amulet or mezuzah containing such letters. Rashi may have meant that certain important demerits of the mezuzah were written in larger characters than the

rest, which indeed we find to be the case with the magical names in many amulets, or he may have referred to the mystical figures, favored in both amulets and mezuzot.23 What is more, we find included in the mezuzah verses which speak of God's protection, names of God and of angels (usually written in large letters), and various magical figures of the type mentioned. In brief—the mezuzah was actually transformed into an amulet, by embodying in it the features which we discovered to be characteristic of these charms.

We may discern a gradual process at work here. Originally, according to Jewish law, the mezuzah was to contain only the prescribed verses; the slightest change, whether of addition or omission, even of a single letter, invalidated the whole. Then, toward the end of the Geonic period the first move to introduce amulet features into the mezuzah was made. The face of the mezuzah was not invaded, but innovations were introduced upon the back of the parchment, concerning which there was no prohibition. The name Shaddai was inscribed there and a tiny window opened in the case so that the name was visible. This name was considered especially powerful to drive off demons, and by the method of notarikon it was read as "guardian of the habitations of Israel." The custom spread rapidly throughout the Jewish world and was adopted everywhere, without a word of censure from the authorities, even the mighty Maimonides agreeing that there was no harm in it, since the name was written on the outside of the parchment.24

At the same time, or perhaps subsequent to this first act of daring, another name was added to the mezuzah, still on its reverse: the 14-letter name of God, Kozu Bemochsaz Kozu, a surrogate for the words Yhvh Elohenu Yhvh of the Shema‘, with which the text of the mezuzah opens. The earliest reference to this practice was attributed in a fourteenth-century manuscript, Sefer Asufot, to the Gaon Sherira; the earliest literary occurrence of this name is in Eshkol HaKofer, by the Karaite, Judah Hadassi (middle of the twelfth century) . Maimonides (in the same century) fails to speak of it, though he refers in detail to other features of the mezuzah. It is likely that he was not acquainted with the practice, or at least that it was not followed by southern Jewry, for Asher b. Yeḥiel (1250-1327), an eminent German scholar who spent the latter part of his life in Spain, stated specifically that it was observed in France and Germany, but not in Spain.25 From this we may judge that there grew up in the Orient two distinct traditions; one, which prescribed

the addition of the name Shaddai alone, made its way to Southern Europe, where it was adopted; the second, adding both names, was introduced in the North (the northern codes all mention both names) . This is not unlikely, for we know that the Kalonymides brought with them to the Rhineland a private fund of mystical tradition of Oriental origin, of which this may well have been a constituent. In time the northern practice invaded the South as well. The 14-letter name also possessed highly protective virtues; before leaving on a journey one would place his hand on the mezuzah and say, "In Thy name do I go forth," thus invoking its guardianship, for the Aramaic word employed equalled numerically the name Kozu.26

The next step marked a decided advance. Despite the stringent prohibition against altering in any way the face of the mezuzah, and the active and justified opposition of most of the authorities, names, verses, and figures were added. The original impetus here too seems to have been Geonic, though the earliest reference to the change was again in Judah Hadassi's work. During the succeeding two centuries mezuzah-amulets achieved a wide popularity; several examples of them have been published by Aptowitzer. Some authorities deviated from the conventional opposition. R. Eliezer b. Samuel of Metz (after 1150 C.E.) voiced only half-hearted disapproval; the Maḥzor Vitry regarded the innovations not merely as private usage, or even customary (as distinguished from the legally required form), but as an integral part of the mezuzah; while the Sefer HaPardes made the additions obligatory, as important, even, as the halachic prescriptions.27 But most of the rabbinic authors unanimously seconded Maimonides’ vigorous and uncompromising condemnation of such tampering with the words of Scripture. By the fifteenth century this attitude had triumphed, and even the mystics and Kabbalists of first rank omitted all reference to the magical mezuzah, or expressly rejected it. From then on we hear no more of it.

Aptowitzer distinguishes three main types of mezuzah-amulets, Palestinian, French and German; the last two are so closely alike that we may regard them as essentially one, but the first is altogether distinct and different. It is interesting that though such mezuzot were known in Southern Europe and Northern Africa, we have no extant examples from these regions. Instead of describing these mezuzot in detail I give here the text of two of them from the

manuscript work Sefer Gematriaot,28 which were unknown to Aptowitzer, and which differ somewhat from those he published. They illustrate clearly the distinctive features of these charms.

On the back of this mezuzah, behind the word והיה of line 3, appears the name שדי.

The first, a "Palestinian" mezuzah, contains the names of 14 and 22 letters (the former on the face instead of the back of the parchment), as well as six other names of God (El, Elohim, yhvh, Shaddai, Yah, Ehyeh), seven names of angels (Michael, Gabriel, ‘Azriel, Zadkiel, Sarfiel, Raphael, ‘Anael), and the Priestly Benediction. The second, of the "German" type, contains the same seven angel names and three more at the end (Uriel, Yofiel, Ḥasdiel), the name Yah, twice, the words of Ps. 121:5, the pentagram and other mystical signs, with Shaddai and the 14-letter Kozu, and more figures on the back.

It would take us too far afield to discuss in detail the minor differences between these versions and those of Aptowitzer, which similarly vary from one another. These variations are apparently idiosyncratic, involving the choice and position of the angel-names and of the names of God, the particular magical figures used, the choice of pentagram or hexagram, etc. The general outline was fixed, the details were apparently subject to the whim and esthetic taste of the scribe. While these two mezuzot are less elaborate than some of the others, they do possess one striking distinction, namely the insertion of circles and once of a ø in the body of the text. The

others were careful at least not to corrupt the Scriptural citation, in which respect they were more closely observant of the prohibition against tampering with the mezuzah.

Sefer Gematriaot29 offers also a detailed mystical apologia for the various unauthorized features, of this nature: the 22 lines correspond to the 22 letters of the alphabet, the ten pentagrams to the ten commandments, and their fifty points to the fifty "gates of understanding" and also to the fifty days between Passover and Pentecost (the "days of the giving of the Law"), the seven angel-names to the seven planets and the seven days of the week, the ten circles to the ten elements of the human body, blood, flesh, bones, etc., five of them to the five names of the soul, the three at the end to the three faculties, hearing, sight and speech, or to heaven, earth and atmosphere, etc. But this rigmarole didn't obscure the true significance of the innovations.

These features make it sufficiently evident that during the Middle Ages the mezuzah acquired all the trappings of the legitimate amulet, becoming one in actuality as well as by reputation. No wonder that Jews regarded it with such respect. No wonder that Gentiles envied them its possession.