Sacred Texts Earth Mysteries Index Previous Next

Buy this Book at Amazon.com

Zetetic Astronomy, by 'Parallax' (pseud. Samuel Birley Rowbotham), [1881], at sacred-texts.com

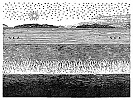

ALTHOUGH the sun is at all times above the earth's surface, it appears in the morning to ascend from the north-east to the noonday position, and thence to descend and disappear, or set, in the north-west. This phenomenon arises from the operation of a simple and everywhere visible law of perspective. A flock of birds, when passing over a flat or marshy country, always appears to descend is it recedes; and if the flock is extensive, the first bird appears lower or nearer to the horizon than the last, although they are at the same actual altitude above the earth immediately beneath them. When a balloon sails away from an observer, without increasing or decreasing its altitude, it appears to gradually approach the horizon. In a long row of lamps, the second--supposing the observer to stand at the beginning of the series---will appear lower than the first; the third lower than the .second; and so on to the end of the row; the farthest away always appearing the lowest, although each one has the same altitude; and if such a straight line of lamps could be continued far enough, the lights would at length descend, apparently, to the horizon, or to a level with the eye of the observer, as shown in the following diagram, fig. 63.

Let A, B, represent the altitude throughout of a long row of lamps, standing on the horizontal ground E, D; and C, H, the line of sight of an observer at C. The ordinary principles of perspective will cause an apparent rising of the ground E, D, to the eye-line C, H, meeting it at H; and an apparent descent of each subsequent lamp, from A, to H, towards the same eye-line, also meeting at H. The point H, is the horizon, or the true "vanishing point," at which the last visible lamp, although it has really the altitude D, B, will disappear.

Bearing in mind the above phenomena it will easily be seen how the sun, although always above and parallel to the earth's surface, must appear to ascend from the morning horizon to the noonday or meridian position; and thence to descend to the evening horizon.

In the diagram, fig. 64, let the line E, D, represent the

surface of the earth; H, H, the morning and evening horizon; and A, S, B, a portion of the true path of the sun. An observer at 0, looking to the east, will first see the sun in the morning,

not at A, its true position, but in its apparent position, H, just emerging from the "vanishing point," or the morning horizon. At nine o'clock, the sun will have the apparent position, 1, gradually appearing to ascend the line H, 1, S; the point S, being the meridian or noonday position. From S, the sun will be seen to gradually descend the line S, 2, H, until he reaches the horizon, H, and entering the "vanishing point," disappears, to an observer in England, in the west, beyond the continent of North America, as in the morning he is seen to rise from the direction of Northern Asia. An excellent illustration of this "rising" and "setting" of the sun may be seen in a long tunnel, as shown in diagram, fig. 65. The top of the tunnel,

[paragraph continues] 1, 2, and, the bottom, 3, 4, although really equi-distant throughout the whole length, would, to an observer in the centre, C, appear to approach each other, and converge at the points, H, H; and a lamp, or light of any kind, brought in, and carried along the top, close to the upper surface 1, 2, would, when really going along the line, 1, S, 2, appear to ascend the inclined plane H, S, to the centre, S, and after passing the centre, to descend the plane S, H; and if the tunnel were sufficiently long, the phenomena of sunrise and of sunset would be perfectly imitated.

A very striking illustration of the convergence of the top and bottom, as well as the sides, of a long tunnel, has been observed in that of Mont Cenis. M. de Porville, when in the centre of the tunnel, noticed that the entrance had apparently become so small that the daylight beyond it seemed like a bright star. "Before us, at an apparently prodigious distance, we beheld a small star at the entrance of the gallery. Its vivid light contrasted strangely with the red glare of the lamps. Its brightness increased as the horses dashed on the way. In a short time its proportions were more clearly defined, and its volume increased. The illusion was quickly dispelled as we got over some kilometres. This soft white light is the extremity of the gallery." 1

We have seen that "sunrise" and "sunset" are phenomena dependent entirely upon the fact that horizontal lines, parallel to each other, appear to approach or converge in the distance. The surface of the earth being horizontal, and the line of sight of the observer and the sun's path being over and parallel with it, the rising and setting of the moving sun over the immovable earth are simply phenomena arising necessarily from the laws of perspective.

127:1 "Morning Advertiser," September 16th, 1871.